︎︎︎

JULIAN NOVITZ

Julian Novitz is a senior lecturer in Writing and Literature at Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne. He is the author of two novels and a collection of short stories (PRH, New Zealand) and his fiction and criticism have appeared in a wide range of journals, magazines and anthologies.

Mind’s Eye

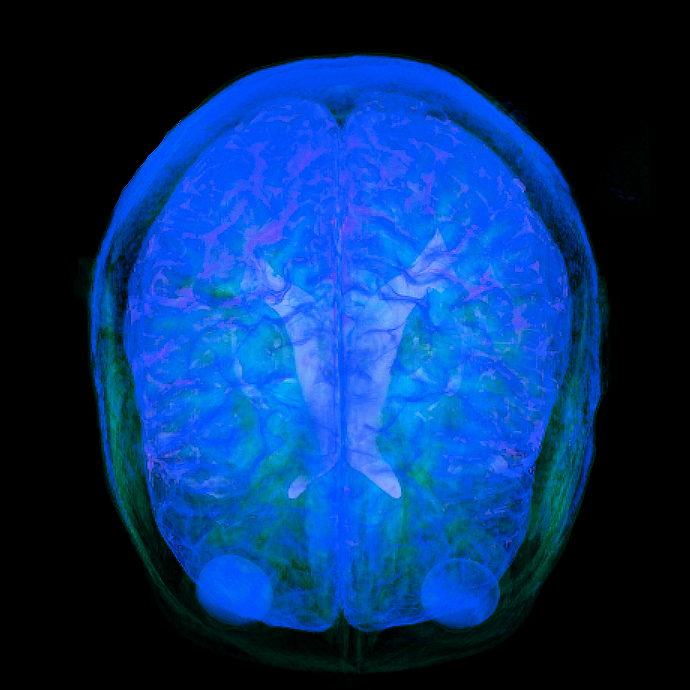

The eyes. It’s difficult for me to reconcile the image of the brain on its own with consciousness. Aristotle was similar, insisting that the heart was the centre of the self, its noble chambers containing our capacity for motion, sensation, and intelligence. The brain, by contrast, is an unassuming organ: wrinkled, faintly absurd, forever underwhelming. Perhaps that’s why we find such pleasure and horror in exposing it. Zombies chewing apart the heads of their victims; innumerable autopsy scenes; Mordred splitting Arthur’s ‘brain-pan’ at the climax of Le Morte d ’Arthur. There’s a transgressive thrill in revealing these small, neat coils of anticlimactic grey matter.

But the eyes - present in this picture, two translucent jelly orbs, hovering above the frontal lobe – transform the brain into something uncanny. A schoolfriend told me that the eyes were part of the brain when I was five or six, and I remember recoiling, horrified but also strangely delighted by the idea that my brain wasn’t hidden and mysterious, but grossly exposed, open to the touch. With the eyes attached, the image of the brain becomes more human and more monstrous, something achingly incomplete. At around the same age, I was transfixed by an old Dr Who serial where the creature of the week was a brain in a globe with distended artificial eye stalks. It looked grotesque to me, but also strangely mournful; the fake eyes without a mouth or face, the brain floating in liquid behind them. One scene stands out, where a mad scientist is transferring the living brain into a new body, and their hulking, deformed lab assistant drops it. I remember the deliciously wet splattering sound, and the visceral cry of sympathetic pain from the actor playing the scientist, the sense of affront to the dignity of the organ. Sometime later, a schoolteacher took to reading Roald Dahl’s Tales of the Unexpected to our class. One story featured a woman whose husband, after an accident, is reduced to a brain and an eyeball preserved in a vat. She proceeds to torment her helpless husband with all the things he had denied her in their married life: music, television, smoking. The last line of the story has the eyeball dilating with fury as she blows cigarette smoke across the glass, and that image has stayed with me ever since. The last flicker of emotion possible when everything else is stripped away.

The eyes. It’s difficult for me to reconcile the image of the brain on its own with consciousness. Aristotle was similar, insisting that the heart was the centre of the self, its noble chambers containing our capacity for motion, sensation, and intelligence. The brain, by contrast, is an unassuming organ: wrinkled, faintly absurd, forever underwhelming. Perhaps that’s why we find such pleasure and horror in exposing it. Zombies chewing apart the heads of their victims; innumerable autopsy scenes; Mordred splitting Arthur’s ‘brain-pan’ at the climax of Le Morte d ’Arthur. There’s a transgressive thrill in revealing these small, neat coils of anticlimactic grey matter.

But the eyes - present in this picture, two translucent jelly orbs, hovering above the frontal lobe – transform the brain into something uncanny. A schoolfriend told me that the eyes were part of the brain when I was five or six, and I remember recoiling, horrified but also strangely delighted by the idea that my brain wasn’t hidden and mysterious, but grossly exposed, open to the touch. With the eyes attached, the image of the brain becomes more human and more monstrous, something achingly incomplete. At around the same age, I was transfixed by an old Dr Who serial where the creature of the week was a brain in a globe with distended artificial eye stalks. It looked grotesque to me, but also strangely mournful; the fake eyes without a mouth or face, the brain floating in liquid behind them. One scene stands out, where a mad scientist is transferring the living brain into a new body, and their hulking, deformed lab assistant drops it. I remember the deliciously wet splattering sound, and the visceral cry of sympathetic pain from the actor playing the scientist, the sense of affront to the dignity of the organ. Sometime later, a schoolteacher took to reading Roald Dahl’s Tales of the Unexpected to our class. One story featured a woman whose husband, after an accident, is reduced to a brain and an eyeball preserved in a vat. She proceeds to torment her helpless husband with all the things he had denied her in their married life: music, television, smoking. The last line of the story has the eyeball dilating with fury as she blows cigarette smoke across the glass, and that image has stayed with me ever since. The last flicker of emotion possible when everything else is stripped away.